| Word Count: 1,387 Estimated Read Time: 5 ½ min. |

Cambridge English Dictionary defines perception as a thought, belief, or opinion often held by many people and based on appearances. So a perception is based on how things appear… how we ‘see’ them with our senses and interpret that information with our minds. However, what we perceive is not always fact. Depending on the context, our interpretation of what we see can give an impression that is different from reality. These can happen with or without malice or intent to deceive.

This happens a lot with design. Something might be made to look either much bigger or much smaller depending on the context in which it is presented. That would be considered an illusion, and there are many different kinds of illusions. Here are some common ones.

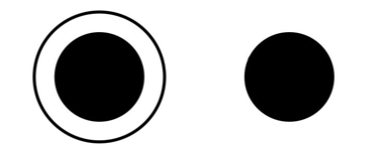

The Delboeuf Illusion – is an optical effect related to relative size perception. If the same circle is placed inside two different concentric circles, its size will apparently vary. This illusion is named after Franz Joseph Delboeuf, a Belgian philosopher, who first recognized the effect. In the best-known example of the illusion, two circles of identical size are placed near each other. One is surrounded by an annalus (or little ring) which is a region bounded by two concentric circles. The surrounded circle then appears larger than the non-surrounded circle if the annulus is close, while appearing smaller than the non-surrounded circle if the annulus is distant.

How might the Delboeuf Illusion be applied in business in a positive way? One positive application might be for weight loss apps and programs. The Delboeuf Illusion has been found to help people moderate how much food they put on their plate for a meal. A 2014 study published in the International Journal of Obesity found that due to the Delboeuf illusion, participants overestimated the diameter of food on plates with wider rims compared with those with thinner rims. And, a 2012 study published in the Journal of Consumer Research, in which researchers asked participants to serve themselves soup in bowls of different sizes, found that individuals poured more soup in larger bowls, on average, than in smaller bowls. The researchers believed the Delboeuf Illusion explained the different behavior. By advising clients to use smaller plates and bowls, weight loss apps could help clients put less food on their plates, thereby eating less and possibly reaching their target weight faster.

Now, how might the Delboeuf Illusion affect businesses and consumers in a negative way? In the case of food packaging, the effect could be used to make something smaller seem bigger. A decade ago, peanut butter manufacturers did just that… not with a circle but with a half-sphere or dimple. In 2008, Skippy peanut butter added a "dimple" in the design of their jars. Instead of having a flat bottom like any normal plastic jar, their jars were suddenly concave — denting inward. The weight of the jar, which had previously been 18oz, became 16.3oz. However, the price did not change. The buyer received 9.44% less peanut butter. Providing nearly 10% less peanut butter in one jar meant the buyer would run out sooner than usual, and buy it more frequently throughout the year without knowing why. In quick succession, the rest of the major peanut butter manufacturers copied Skippy’s design dimple. This is a classic example of the Delboeuf Illusion… making something that was smaller seem bigger by altering the space around it.[1] This benefited manufacturers and grocery chains who had customers returning to the store more often. It did not, however, benefit consumers or businesses that used peanut butter as part of what they provided to customers.

Peanut butter manufacturers weren’t the only food packagers who made use of the Delboeuf Illusion. In Priceless: The Hidden Psychology of Value, William Poundstone explained that consumers might switch peanut butter brands if the price went up, but did not switch brands if the jar shrunk but the price stayed the same.[2] That would explain why, that same year, Kellogg also made thinner cereal boxes for brands such as Cocoa Krispies, Fruit Loops, and Apple Jacks. However, they kept the width, height, and price the same. The result is that no one really noticed. There was no major public outcry. Consumers did not examine the label to see how much food was in the box compared to before. People trusted their eyes and the price seen over and over again.

The Ebbinghaus Illusion – Another common optical effect is the Ebbinghaus Illusion, also referred to as the Titchener circles. This effect is related to relative size perception. When two circles of identical size are placed near to each other, and one is surrounded by large circles while the other is surrounded by small circles, the result of the juxtaposition of the circles is that the central circle surrounded by large circles appears smaller than the central circle surrounded by small circles.

This illusion was named after its discoverer, German psychologist Hermann Ebbinghaus (1850-1909). However, it became well-known in the 20th century when Professor Edward Titchener added it to his 1901 experimental psychology textbook.

There seems to be two critical factors involved in the perception of the Ebbinghaus illusion. These are the distance of the surrounding circles from the central circle and the completeness of the annulus, similar to the Delboeuf Illusion. Regardless of relative size, if the surrounding circles are closer to the central circle, the central circle appears larger and if the surrounding circles are far away, the central circle appears smaller. While the distance variable appears to be an active factor in the perception of relative size, the size of the surrounding circles limits how close they can be to the central circle.

The Ebbinghaus Illusion is often used in a negative way in TV and printed media advertising. In 2008 in the UK, a furniture store owner was told by the Advertising Standards Authority (ASA) to withdraw his advertisement from TV broadcast because of the false impression it gave to the viewers about the true size of the sofa. DFS used green screen technology to manipulate the size of actors superimposed into the advertising video, which made the sofas placed next to the actors look larger than they really were. However, interventions by government entities in the U.S. and abroad on the grounds of an illegitimate use of Ebbinghaus Illusion in advertising is rare. Advertisers get away with similarly blatant manipulation of product size for marketing purposes. That said, the use of the Ebbinghaus Illusion is not limited to marketing.

Also, it has been used in a positive way by companies to reflect the value of money. The perceived value of money is determined by the comparison between the subject (money) and the anchor or context in which a valuation takes place. Therefore, the perceived value of money can be affected by influencing the context in which the valuation takes place. For example, a brand-name purse priced at $100 might seem expensive in a suburb of Newark. But, if that same purse were sold in Manhattan, then it might seem like a bargain if found at a shop on Fifth Avenue.

Perception versus Reality

Given that what we see, hear and read in the world is just a perception – one that can be distorted by our own experiences, thinking errors and optical illusions of which we are likely not aware – then leaders must careful with the decisions they make based on what seems to be real. The key is to seek other validation that confirms that what seems real is in fact true. As companies look to shape perception of their own brand and make business decisions based on perceptions, the key is to dig a little deeper – and look beyond the surface – to validate if the perception is reality. After all, things are not always what they seem.

Case in point. Recently, Kathryn Minshew, CEO of The Muse – a career platform and job discovery tool serving more than 5 million professionals — said “People actually aren’t moving on from companies much more quickly than in the past, but there’s a perception that they do, so companies are investing less in talent on the assumption that young employees won’t stay long.” The perception of high Millennial turnover is causing companies to invest less in people, which could in turn increase turnover thereby turning a perception that was not true into an unfortunate reality.

Quote of the Week

"Your opinion is your opinion, your perception is your perception – do not confuse them with “facts” or “truth”. Wars have been fought and millions have been killed because of the inability of men to understand the idea that EVERYBODY has a different viewpoint." John Moore

[1]September 28. 2016, Lee Breslouer, You’re Getting Cheated Out of Peanut Butter, Thrillist, https://www.thrillist.com/eat/nation/peanut-butter-jar-size-prices-explained

[2] Poundstone, William, The Hidden Psychology of Value, Published by Oneworld Publications, 2010.

© 2019, Keren Peters-Atkinson. All rights reserved.